Naimat Nigaar on Post-colonial Behaviour and Treaties

Naimat Nigaar begins the discourse by speaking about his home, Loralai, and his current residence in Lahore. His mixed media commentary is reflective, scanning urban infrastructure, social practices and human rhythms. His work sets the vast horizontal plains of Baluchistan against the dense vertical edifices of Lahore. These striking spatial intensities are juxtaposed through the shades of open earth and the surreal defiance of skies, the measured flow of lines and the urgency crammed in shapes.

This visual dialogue connects materials with political narratives, and the manner in which communities engage with them in their environments. One such instance seen in Naimat’s work is the use of rich colors of Baluchistan’s minerals – such as the brownish-black of coal – as a subtle reminder of undocumented immigration in the region, child labour and shadowy mining acts, all employed for unethical exploitation of land. From Baluchistan to Congo, agreements are dictated by elements of a post-colonial mindset. The East India Company historical metaphor is applied here to trace patterns of dominating indigenous territories through unfair treaties. He remarks that when we talk about injustice, we should address it everywhere. To pick and choose is unfair — as a nation, we speak out about Gaza but often ignore KPK and Baluchistan. The exploitation of minerals follows a familiar pattern; the history of colonization is deeply entangled with the presence of natural resources, always overlooking the rights of the indigenous communities.

Collaborations and workshops add to Naimat’s experience, where he has observed that regional disparities always surface, regardless of whether people try to hide them. In a post contemporary era, human behaviours responding to materials and objects are specific, and likely shaped by political memories, which are distorted due to propaganda and information control. He cites an example here: He had a cantonment studio in Lahore, which had a checkpoint at the entrance, since cantonment personnel are more vigilant about who enters rather than who exits. One of his junior students visited him on a Friday, wearing a Baluchi shalwar kameez, and was asked for identification because of his attire. This kind of recognition based on the materials we wear and the objects we possess extends across all industries. Similar distinctions (class-based or otherwise) are evident in global trends like Beanie Babies and Labubus, which reflect underlying social anxieties and insecurities.

Naimat recounts another occasion in Peshawar when one of his friends, visiting from Lahore, showed his identification to a soldier who was also from Lahore and was allowed to pass inspection. He then hints at the various hierarchies among the 5,000+ registered madrassas and the privileged classes. He goes on to talk about a mindset shaped by poor policies and widespread illiteracy — an inability among people to look past political parties in favor of achieving common goals. This has been brewing for a long time and is now reaching a breaking point. Adding to this cauldron is the unprecedented progress of technology and social media platforms being repurposed to raise awareness about undocumented disappearances destroying families, while also widening the gap in understanding between generations due to nonlinear experiences.

The circumstantial, haphazard, and disjointed nature of our scars, difficult to justify and could have been avoided, is seen in the stitches in Naimat’s work — always raw, never given the chance to heal.

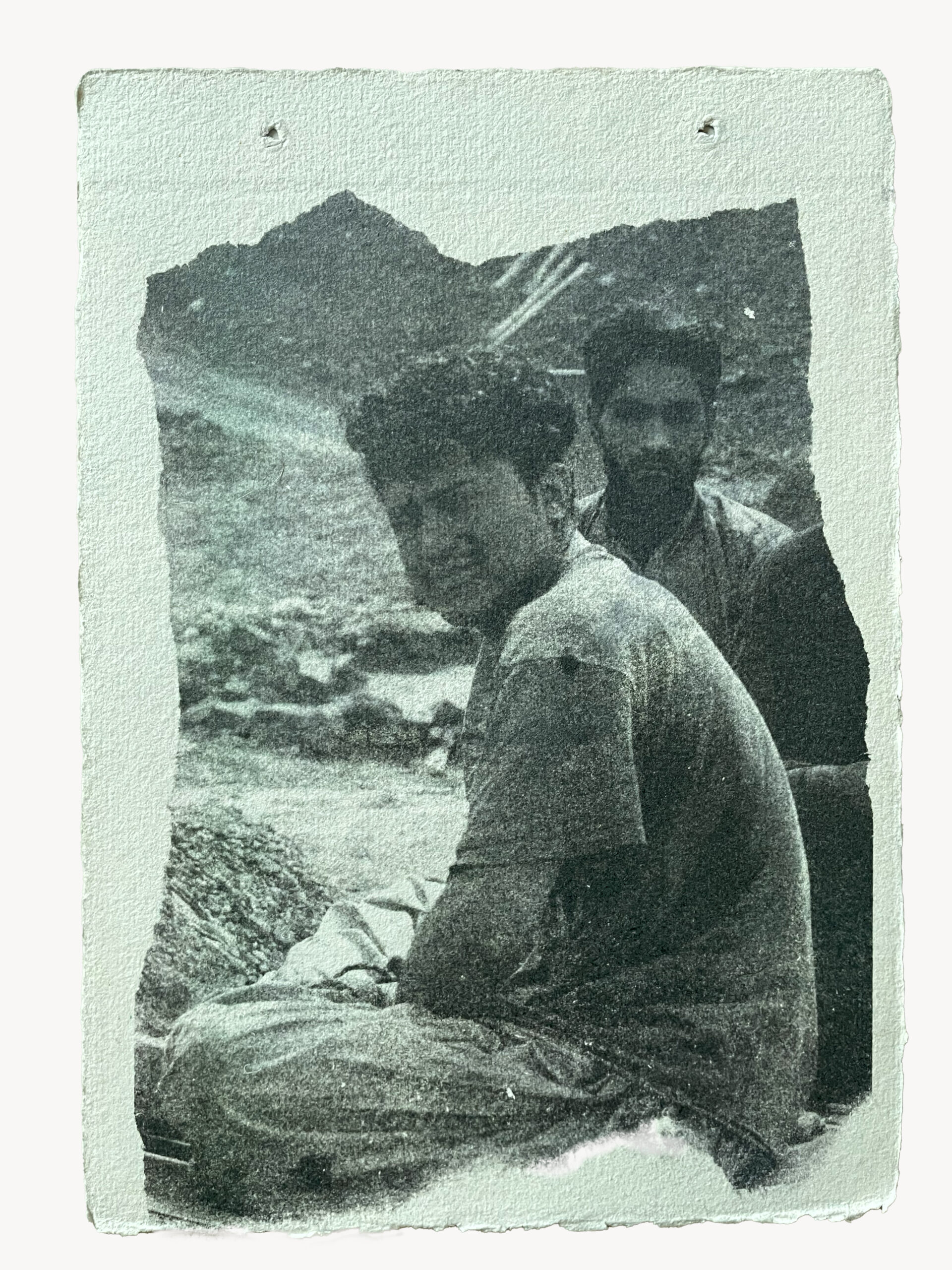

Image: Porters, Niamat Nigaar, Xerox Print on Handmade Paper, all copyrights are retained by the artist, 2025